The foundational cracks in the Union over slavery and the issue of States’ Rights were necessarily exploited by a parade of Southern nationalists promoting a narrative passionate enough to stir men to action, move them into the streets, beat the drums, shout down the opposition, and ultimately to line up in rows and march into withering musket fire. It was a narrative fed by the wealthy, but never wealthy enough, planters and merchants; a narrative endorsed by compliant pastors of limited conscience who had long forgotten the yearning for freedom that drove their forefathers to fight England for independence.

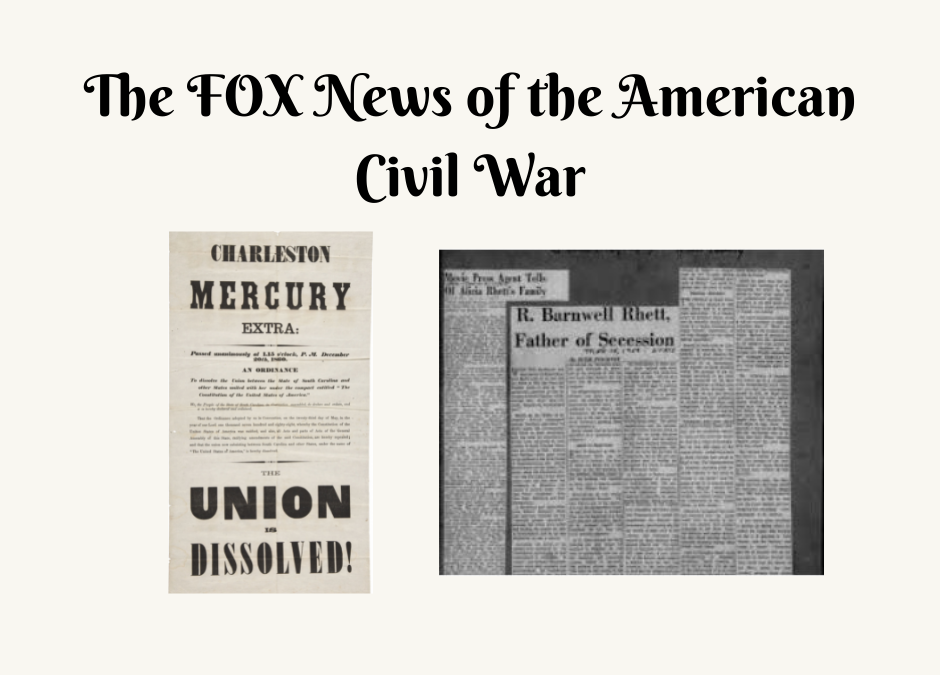

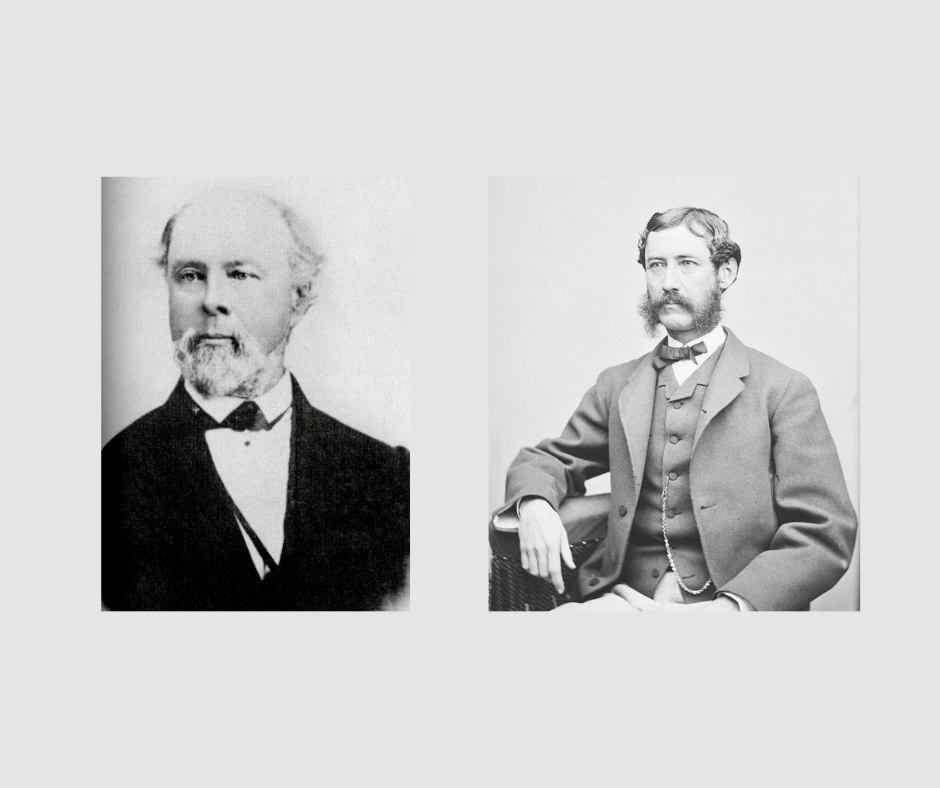

Two of the most influential Southern nationalists were the insurrectionary newspapermen, Robert Barnwell Rhett, Sr. and Jr., who owned and edited the Charleston Mercury. The senior Rhett purchased the Mercury with money obtained by mortgaging slaves from his plantation. Robert Barnwell Rhett, Sr. was a fire-eater who dreamed of being the president of a new Southern Republic. The younger Rhett was editor-in-charge peddling the message of severance to a pliable public with incautious fanaticism. Southern secession was their goal and they stooped to all manner of rascality to achieve it.

While Rhett Sr. was a fire-breathing ideologue, Rhett Jr. was a Southern-fried Machiavelli, an expert in the black art of propaganda. The Charleston Mercury served the public a constant dose of twisted news, cunning insinuation, and the hammering of secessionist themes.

“Barny” Rhett, Jr. was a skilled caricature artist who understood that the virtue of secession required an equally formidable vice to set itself against. That foil would be the repugnant nominee of the “Black Republican Party,” Abraham Lincoln. Ignoring Lincoln’s basically even-handed legislative record, the editorial page of the Charleston Mercury screamed that Lincoln was a full-blooded abolitionist with a heart as hard and black as onyx. Rhett’s caricatures portrayed Lincoln with a stooped, long-armed, monkey-like posture, with heavily shaded skin and a raggedy dress suggesting a lack of purity in his bloodline. The Charleston Mercury described Lincoln as “sooty and scoundrelly in aspect: a cross between the nutmeg dealer, the horse swapper, and the night man.” I am not sure what each of those names implies but, I am fairly certain they were heard as dog whistles in the day.

The Scotch-Irish workingmen of Charleston were continuously threatened with the loss of what little they had to free slaves with even less. The Charleston Mercury also turned the easily twisted screws of regional pride, state allegiance, resistance to Federal intrusion, and the Godly protection of the Southern way of life and the plantation economy. “Barny’s” editorials neglected to point out the historical reality that these same working-class whites would be the ones fighting and dying to preserve a right to property they did not own and never would.

Roger Newman’s new Civil War historical fiction novel – Will O’ the Wisp: Madness, War, and Recompense – explore the forces that led to South Carolina’s secession from the Union and the consequences of that rebellion to the people of Charleston and the South in general. Much of what happened in Charleston preceding the firing on Fort Sumter resonates with the polarizing discourse seen in the newspapers and television shows in today’s media.

Will O’ the Wisp: Madness, War, and Recompense is available on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Kindle, and Ingram.