Cases of severe fetal microcephaly in Brazil have risen from fewer than 150 in 2014 to almost 4,000 in 2015. This surge in an otherwise rare fetal brain malformation has been linked to the Zika virus. The what? Yes, the Zika virus. Concern over this possible epidemic has led to a spate of articles in the popular press and the recent release of interim guidelines from the Center for Disease Control (CDC), American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM).

In my career I’ve seen such “epidemics” happen before in the perinatal world- Hepatitis B, HIV, Herpes, Swine flu, Bird flu, Parvovirus, Pertussis, Ebola and now Zika. Lessons learned? Plenty of reason to be concerned, but so much is currently unknown that the true risk cannot yet be estimated. Time to be educated; not panicked.

What do we know? Zika virus is mosquito-borne virus transmitted primarily by the Aedes aegypti mosquito which also carries dengue fever and the chikungunya virus. These mosquitoes are found throughout Central and South America as well as southern parts of the United States. Most acute infections are asymptomatic. Only 1 out of 5 women with an acute Zika infection will have relatively mild symptoms consisting of fever, a maculopapular rash, joint pain or non-purulent conjunctivitis. The time between exposure and symptoms (if they occur) is 3 to 12 days. The symptoms usually last a few days to a week.

We also know that the Zika virus can cross the placental barrier to the fetus in all trimesters of pregnancy. The Zika virus has been detected in tissues collected from fetal losses suggesting an association between maternal infection and miscarriage. Mostly importantly, Zika virus infection has been confirmed in a large number of infants born with microcephaly. Microcephaly is a small head due to damage and destruction to the brain tissue. The brain injury associated with Zika virus microcephaly is severe and similar to that seen with other congenital viral infections.

However, what we don’t know about congenital Zika virus infection is even greater. We don’t know:

- The incidence of Zika virus infection among pregnant women in areas of endemic Zika virus

- If pregnant women are at greater risk of Zika infection than non-pregnant women

- If pregnant women experience a more severe infection during pregnancy

- The rate of maternal transmission to the fetus (generally less than 50% for most viruses and in some cases, substantially less)

- The rate at which maternal transmission results in fetal infection and complications such as microcephaly or fetal demise. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is considered the most common congenital viral infection. The CMV transmission rate to the fetus is about 50%, and of those, only about 10% show evidence of symptomatic disease (including brain damage) at birth.

- How many of the reported fetal losses and microcephaly cases are associated with Zika virus

- What role do other contributing factors such as genetics, nutrition, fever, or co-infection may play in determining outcome

- The accuracy of available testing for Zika virus. RT- PCR is diagnostic for maternal viremia but is only positive for a brief window of 3-7 days after the onset of symptoms. After that, serology is necessary to document evidence of a recent infection. Immunoglobin M (IgM) and neutralizing antibody testing, however, are non-specific, frequently cross-reacting with other related viruses such as dengue and yellow fever

- Where to even have the testing done. Commercial assays are not available. Current Zika virus testing is only done at the CDC Arbovirus Diagnostic Lab and a few state health departments

- Of any vaccine or specific treatment for Zika virus

So, given these limitation in our knowledge, what should pregnant women do?

What if you’re CONSIDERING TRAVEL to an endemic area of Zika transmission? DON’T GO. If you find yourself in such an area by mistake, then wear long sleeved shirts and pants, sleep in air-conditioned or screened-in rooms, use FDA recommended (safe in pregnancy) insect repellants (DEET, picaridin, and IR3535) and permethrin-treated clothes both day and night.

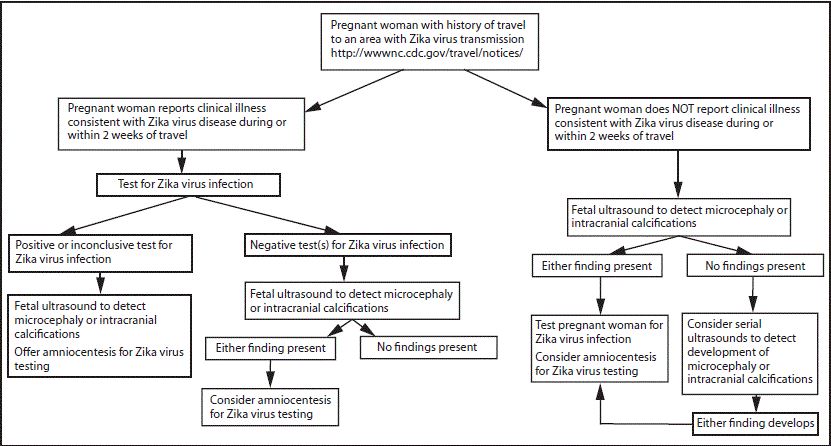

What if you’ve recently TRAVELLED TO an endemic Zika transmission area- and are now HAVING SUSPICIOUS SYMPTOMS? Test your blood for viral particles (Zika RT-PCR) if symptom onset occurred within the past week. IgM serology and neutralizing antibodies should be obtained if it has been 4 or more days since the onset of symptoms. Serial ultrasounds every 3-4 weeks should be done to assess for microcephaly or intracranial calcifications. These ultrasounds should be done by a Maternal-Fetal Medicine specialist or at a tertiary care center doing advanced and detailed fetal imaging. Amniocentesis for Zika virus testing in the amniotic fluid is recommended for women with suspicious fetal ultrasound imaging to confirm fetal infection.

What if you’ve TRAVELLED TO an endemic Zika transmission area but are NOT HAVING SYMPTOMS? This is the tricky one because, AS OF NOW, routine testing for maternal infection is not recommended in the absence of symptoms. However, serial fetal imaging is advised even if you are asymptomatic. The concern is that in low risk patients (ie. no symptoms and no ultrasound findings), the limitations of the current testing (high false positive rate) may cause more harm than good. Testing is not reassuring if it is wrong as often as it is right. To be frank, right now we do not know the reliability of the limited Zika virus testing that is available.

Lastly, what if a DIAGNOSIS of Zika virus is made? There are no specific antiviral treatments available and no way to prevent fetal infection. Rest, hydration, and Tylenol for fever are all recommended as supportive measures. Serial ultrasounds are advised to detect fetal damage as described above. Maternal – Fetal Medicine consultation is recommended given the complexity of the diagnosis and the potential severity of any ultrasonographic findings. The infection does not appear to be transmitted orally. Although the Zika virus has been found in breast milk, it is unlikely to be harmful for the newborn. Breastfeeding is not contraindicated.

We still need to learn an immense amount about this viral infection. How often does the virus cross the placenta? How often does the virus cause fetal damage? What is the mechanism of fetal injury? If a fetal loss occurs or there are newborn abnormalities possibly associated with Zika virus then the state health department should be notified. A detailed assessment needs to be performed including examination of the placenta, umbilical cord and fetal tissue (if available) for Zika virus RT-PCR, histopathology and immunohistochemical staining. Newborn cord blood should be tested for Zika virus IgM and neutralizing antibodies.

This blog post is being published off schedule to get this information disseminated as soon and as widely as possible. We saw a suspicious case in our office this Friday. When we called the state health department they told us to call back next week and they would have a procedure figured out by then. A management algorithm from the CDC is provided as a reference above. Continue to keep an eye out for updates from CDC, ACOG or the SMFM. They will certainly come. My experience is that the consequences of this potential epidemic will prove less threatening than some of the early reports have suggested. I certainly hope so anyway.

I am a Professor of Ob-Gyn at the Medical University of South Carolina, an Endowed Chair for Reproductive Sciences and former President of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. However, this is a personal blog and represents my opinions and not necessarily those of my employer.