The real hero of my new Civil War historical fiction novel is the Charleston-based blockade runner, “Will O’ the Wisp.” Constructed at the F.M. Jones Shipyard on Shem Creek by master shipwright and captain, Jack Whitesides Holmes, the “Will O’ the Wisp” was the most elusive and successful of all the blockade runners based in Charleston.

Lincoln’s decision to blockade Southern ports meant that the large European steamships could no longer enter Southern ports without being taken prizes of war. The South needed iron, lead, munitions, arms, and other industrial products in order to match the more industrialized North. To obtain those goods, the South would need to trade its greatest resource, Sea Island Cotton, also known as “white gold.” Without massive European support, any conflict with the North would eventually devolve into a war of attrition which the South could not survive. To maintain this European trade, the South turned to a fleet of fast and stealthy blockade runners who left Charleston on dark, moonless nights with their bellies and decks stuffed with cotton, timber, and turpentine destined for Bermuda, Nassau, and Cuba where they exchanged cargos with the large European transatlantic steamers.

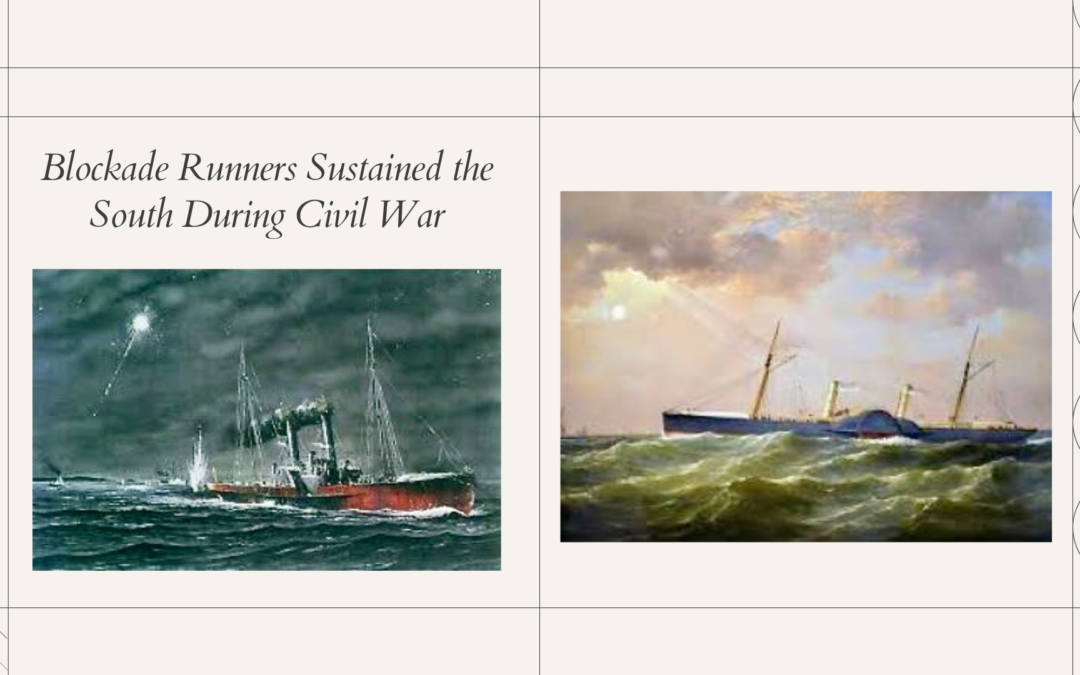

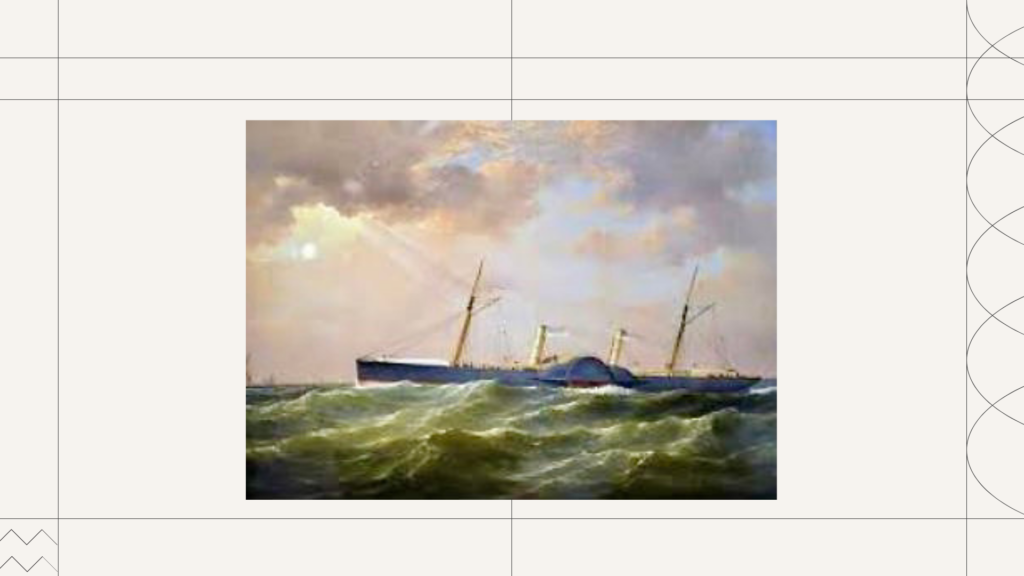

The Will O’ the Wisp was a dual side paddlewheel steamer with the graceful lines of a yacht. She was 190-feet in length, 22-feet across the beam, and drew only 9-feet of water. Her hull was Lowcountry live oak and red cedar harvested from the timber-rich Christ Church forests along the Wando River. The pilothouse was located just behind her sharply angled and telescoping smokestacks which could be lowered to the deck minimizing the ship’s stamp on the horizon. The long, low hull only showed eight feet above the waterline and was painted a dark blue-gray. The low silhouette and minimal masting allowed her to be overlooked at dusk and virtually disappear at night. Even during the day, her blue-gray color blended with the sea and sky at the merge of the horizon.

The “Will O’ the Wisp” burned clean Welsh anthracite coal yielding only white smoke and when steam had to be blown off, it was done underwater to muffle the sound. Heavy tarpaulins were used over the paddle boxes to suppress the rhythmic beating of the paddle floats and over the hatchways to obscure the light from the engine rooms. Even the pinnacle was shrouded so that only the helmsman could peer into a small conical aperture to read the compass. When on a run, the “Will O’ the Wisp” became a black hole in the water.

What the “Will O’ the Wisp” did not carry was even an eighth of an inch of iron plating or any heavy weapons. Captain Jack relied on stealth and his knowledge of the Lowcountry coastline and had no intention of ever exchanging fire with the fearsomely armed Union blockaders. Speed and invisibility were his advantages and the lack of armor assured that the Wisp could outrun anything in the Atlantic Blockading Squadron. When spurred to a gallop the Wisp’s powerful engines could push her a maximum sprinting speed of fifteen to sixteen knots. No other captain in the large Charleston blockade running fraternity enjoyed more success and respect than Captain Jack Holmes.

For more information about the adventures and essential contributions of the Southern Civil War, blockade runners check out my new book, “Will O’ the Wisp: Madness, War, and Recompense” by Roger Newman.