In every discussion of my new book, Will O’ the Wisp: Madness, War, and Recompense, the conversation eventually turns to the enigmatic Confederate President, Jefferson Davis. History has not been kind to Jefferson Davis as the leader of a failed insurrection that stripped the South of its wealth and influence and left it impoverished and angry for generations. Many Americans, both in his own time, as well as in later generations, considered Davis an incompetent leader and a traitor. It is sobering to consider that had he been successful our nation would have been torn in two and the institution of slavery preserved.

In Roger Newman’s new Civil War historical fiction novel, Jefferson Davis is continually in the background making decisions regarding the Southern war effort and establishing economic policy with his financial advisor and eventual Secretary of the Confederate Treasury, George Alfred Trenholm.

George Trenholm was the king of the Southern cotton cartel and the richest man South of the Mason-Dixon line. Trenholm argued that the Southern leaders needed to separate hubris and magical thinking from a clear vision and a realistic business prospectus. He believed that contempt for the Yankees had blinded too many Southern leaders, including President Davis, from seriously considering the South’s industrial constraints and needs.

President Davis’ reckless miscalculations began at the very beginning of the war. Davis believed that a Civil War would cost the Union both Southern trade, as well as trade from other Southern-leaning border states. Davis estimated that Lincoln would bend to Northern business interests who would counsel appeasement instead of economic confrontation. Davis was wrong and Lincoln imposed a blockade of the Southern ports immediately after the shelling of Fort Sumter. More significantly, Davis made the early decision to withhold Southern cotton from the international market. Jefferson believed that the huge textile mills of Northern England and France, starving for raw material, would force their governments to, at least recognize the Confederacy, if not actually join the war as a Southern ally.

Although he had not been a fire-eating secessionist, Jefferson Davis committed himself to preserve an independent Confederate nation. To his credit, he never deviated from that goal, and in a very literal way, was the last Confederate standing when taken into custody in 1865. However, his failings in terms of economic and business acumen, pragmatic governance, and interpersonal skill undermined his ability to confront the limitations of an agrarian South and doomed his Presidency and Southern secession. sharp and menacing, his face narrow with sweptback hair as if in flight, constantly searching the ground for snakes or field mice. By the war’s end, he was thin to the point of gauntness and wore stacked riding boots to appear taller than he actually was. His cheeks were hollow and his skin yellowed to the color of old ivory. He presented himself in profile to hide his milky, useless, left eye. Even his good eye had the distant and disinterested cast of a defeated man.

That cotton embargo would become a cataclysmic mistake. The cotton embargo starved the South of European cash and investment for the first two years of the war. Rather than banking the gold necessary to wage war against a more populous and industrialized North, Davis continued to believe that Lincoln would lose his nerve and that England would decide to enter the war on the Southern side. Neither was likely. Wish in one hand and spit in the other and see which one fills up quicker.

While many of his economic decisions were dim-witted or fell victim to Davis’ well-known recalcitrance, it is only fair to note that many historians praise his military tactics and the relationships he developed with his Confederate Generals, particularly, Robert E. Lee. He devoted his time to a tenacious hands-on influence in the shaping of military strategy. While the South ultimately lost the Civil War, there are few who argue that he was responsible for losing it. A more salient argument is that his bull-headed commitment to a military victory went on long after it was apparent that defeat was inevitable. Negotiations regarding surrender were consistently frustrated by the single issue on which President Davis would not compromise. That issue was his insistence on Southern independence. After all, you can’t hang the President of another independent country.

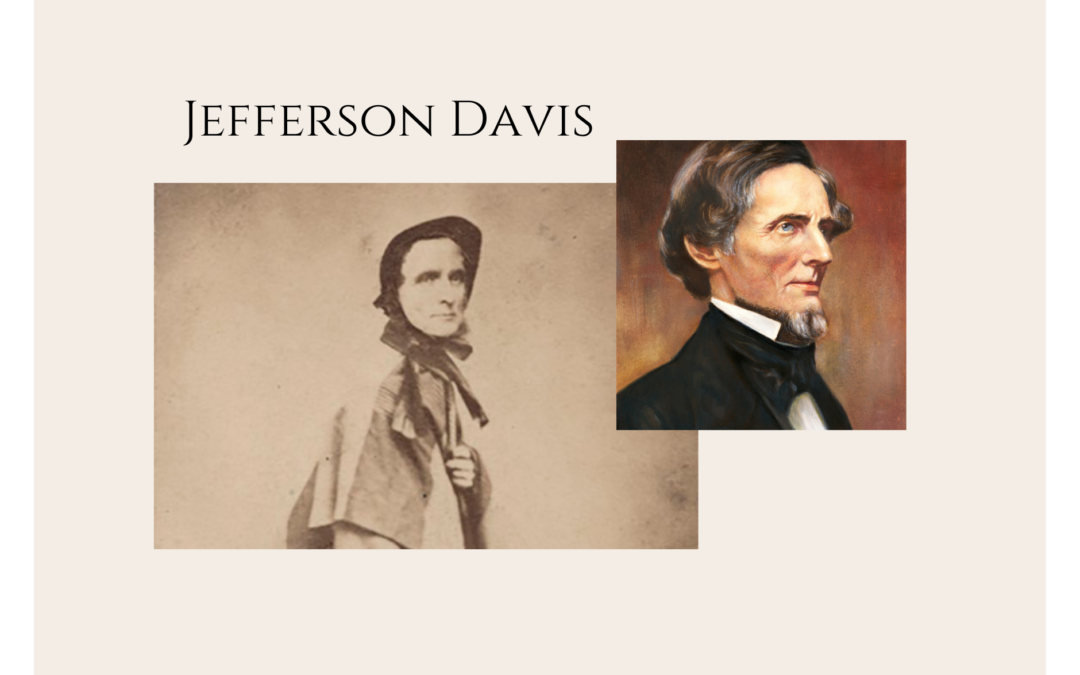

Like many other flawed leaders, Jefferson Davis lacked the interpersonal skills to either inspire or lead. He was humorless and hard to reach on a personal level. He was typically disengaged unless the topic involved matters of politics which stirred him to ambitious zeal. His subordinates and enemies alike considered him difficult, egotistical, and cold. In addition, the war took a tremendous toll on the Southern President. As a young man, he had been likened to a predatory raptor. A hawk-like nose, eyes sharp and menacing, his face narrow with sweptback hair as if in flight, constantly searching the ground for snakes or field mice. By the war’s end, he was thin to the point of gauntness and wore stacked riding boots to appear taller than he actually was. His cheeks were hollow and his skin yellowed to the color of old ivory. He presented himself in profile to hide his milky, useless, left eye. Even his good eye had the distant and disinterested cast of a defeated man.

By the time he was captured in Georgia after the war’s end, he had taken to dressing in women’s clothes to disguise his identity. Many Confederates wondered how they could have pledged their loyalty to, and marched to war for, a man so preening and lacking in confidence that he wore elevated riding boots and would dress as a woman to avoid capture.

Although he had not been a fire-eating secessionist, Jefferson Davis committed himself to preserve an independent Confederate nation. To his credit, he never deviated from that goal, and in a very literal way, was the last Confederate standing when taken into custody in 1865. However, his failings in terms of economic and business acumen, pragmatic governance, and interpersonal skill undermined his ability to confront the limitations of an agrarian South and doomed his Presidency and Southern secession.

For more discussion of the Southern politics that preceded and followed secession please consider reading “Will O’ the Wisp: Madness, War, and Recompense” by Roger Newman, available at Amazon, Kindle, and Barnes and Nobel.