The pinnacle of haute cuisine in pre-war Charleston was the successful presentation of a silver tureen of terrapin stew. The name terrapin itself comes from an Algonquian Indian word that translates as “good tasting turtle.” Terrapin stew had been originally eaten by the slave populations of the Tidewater area between Virginia and Maryland. The soupy stew was served over starch of African origin and was a cousin of Creole gumbo. Over time, the African food traditions were appropriated by the white masters.

The king of all turtles was the Chesapeake Bay Diamondback Terrapin but those were hard to come by during the Civil War. However, locally, the Shem Creek snapper made for an extremely fine substitute. Up North, people preferred Philadelphia-style turtle soup with heavier cream and mace. The added cayenne and ground white pepper, however, could overpower the mild flavor of the turtle meat. In the Mid-Atlantic, they preferred a Baltimore-style which was clearer with a buttery broth, but somewhat bland. The favored version of the Charleston’s elite was a New Orleans -style with a darker roux, a spicy tomato broth, and more piquant Creole spices.

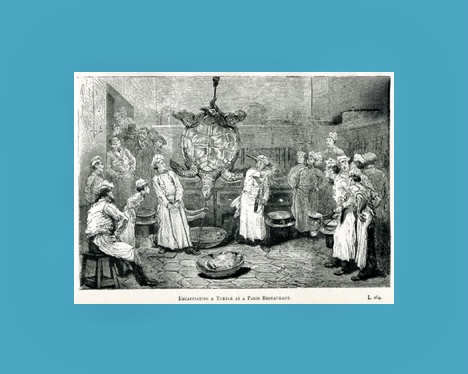

The culinary effort necessary to successfully prepare terrapin stew is quite complex. The turtle’s head is severed and the carcass hung upside down to bleed out. Experienced butchery was required to disassemble the turtle removing the nails, scales, and shell along with the entrails. An absolute key was making sure that the gallbladder was not perforated which would impart a bitter taste to the turtle meat. If fortunate enough to find eggs inside a she-turtle, they would be hard-boiled and added to the stew. If not, hens eggs could be substituted.

When served, the stew was topped with a sprinkling of finely chopped spring onion tops, parsley, dill, and celery leaves. Croutons crisped in duck fat were also offered. Depending on the preference of the guest, the presentation could also be topped with a dram of sherry or brandy. A special terrapin fork was part of each place setting with a bowl for the soup broth and a single tong for the turtle meat. In antebellum Charleston, the ability of a man such as George Alfred Trenholm to have a slave with the talent to prepare such a sophisticated fine dining dish was a matter of societal prestige.

To learn more about the people of Charleston and their lives and actions before, during, and after the Civil War please consider reading my new book, “Will O’ the Wisp: Madness, War, and Recompense.”