Many books and stories have focused on the politics and passions that inflamed the South and resulted in the Civil War. Scarlett O’Hara is put out by the revolutionary zeal and secession excitement that ruins her coming out party at Tara. Puffed up by narrow self-righteousness, Southern men rushed off to a war they felt certain to win in months, if not weeks. Far less literary attention has been paid to the destruction and deprivation that would follow the rashness of that decision.

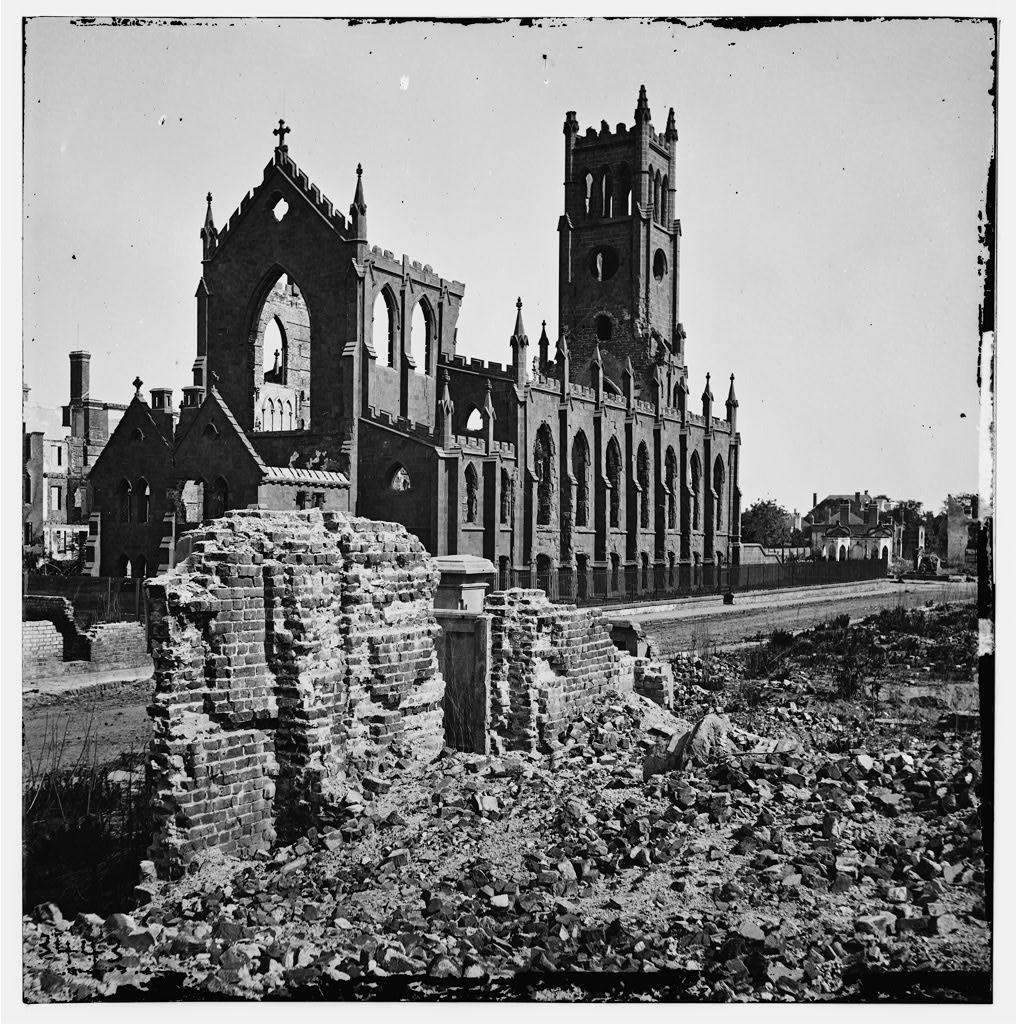

Charleston wore its distinction as the epicenter of righteous rebellion like a badge of honor. Charleston’s fire eaters, politicians, pastors, newspapermen and the favored had demanded the breaking of ties that had knitted the Union together. Citadel cadets waving their red battle flag fired the first hostile shots of armed rebellion. Charleston had instigated a betrayal that the North would not forget or forgive.

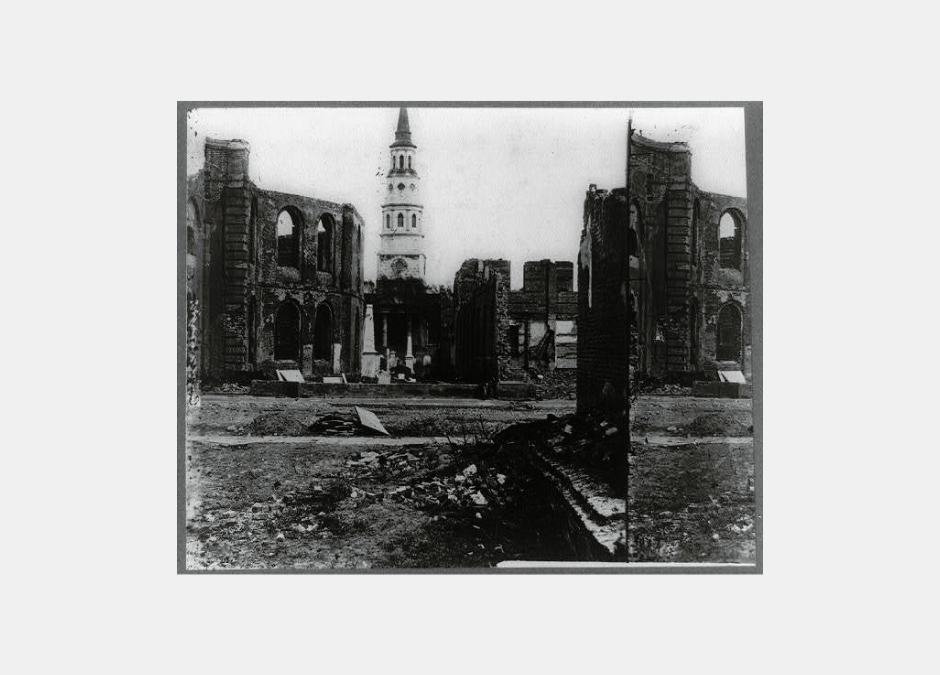

For most of the war, Charleston was insulated from the war’s mayhem and mauling. Other than a fire that swept across Charleston’s lower peninsula on a windy December evening in 1861, most of the Holy City’s gardenia and magnolia blossoms had not experienced a single bruise. Even that fire was accidental. arising from a cook fire beneath an East Bay Street dock and driven west by strong winds down Broad and Queen Streets destroying everything in a mile long path.

By spring of 1863, however, the pinch of the Union blockade was no longer an abstract concern. New Orleans had fallen to a Union naval attack, effectively cutting the Confederacy in half along the Mississippi River. That loss resulted in denying Texas beef cattle to most of the Confederacy. General Lee’s attempt to take the war to the North resulted in a demoralizing defeat at Antietam, Maryland in September of 1862. An emboldened Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1st, 1863, freeing all slaves in the rebellious Southern states. Obvious to anyone paying attention, the South was losing. What Lincoln had begun as a war of reunification had now become personal and punitive. Charleston was going to pay a steep price for its disloyalty.

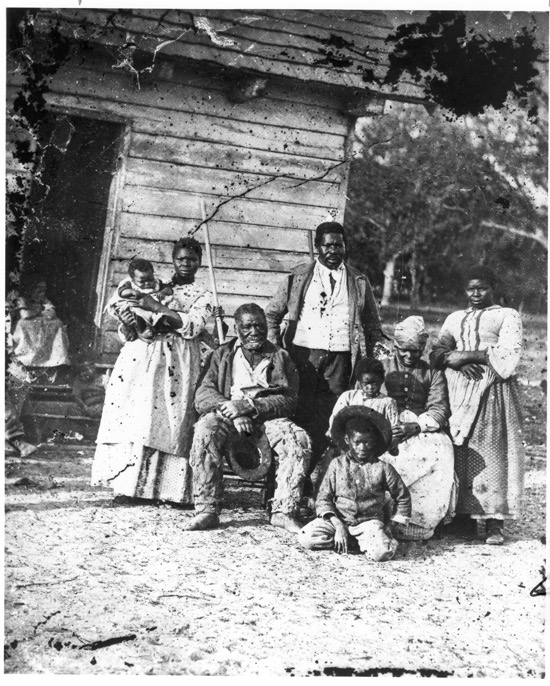

The summer of 1863 brought deprivation to Charleston that had never been envisioned during the heady days of secession. The South Atlantic blockade and the escalating needs of the Confederate army had created severe shortages of both food and merchandise. Families were pulling forgotten spinning wheels down from the attics. The hum of the wheel and the clang of the loom were new communal sounds. Black house slaves taught their white matrons how clothing dyes could be squeezed from bark, leaves, roots and berries and how to carve and polish buttons from cross-sections of small wood branches. Working-class white women and house slaves with sewing skills found new employment sewing coats, shirts, pants, tunics, blankets, and quilts.

On the dinner table, corn meal replaced wheat flour. When the corn meal was unavailable, families took to grinding and roasting peach pits to make a peach pit flour. Roasted peach pit flour had a pleasant cherry or sweet almond-like smell, but unfortunate improvisors discovered that peach pits could poison if incompletely roasted. Peanut oil replaced whale oil for the house lamps. A thick sugary syrup from watermelons replaced cane sugar. Plantation slaves tanned the hides of horses, mules, and hogs with red oak bark to make “country leather.” Mixing cottonseed oil with soot made for a fine shoe black and everyone dipped their own candles.

Slave women with knowledge of woodland herbs or swamp flora became valuable commodities since medical supplies were non-existent. In the slave communities there was an herbal remedy for virtually every ailment. Every kitchen in Charleston had a pantry filled with pickled vegetables and canned fruits. Downtown, afternoon tea was steeped from from dry raspberry and blackberry leaves and a passable coffee could be brewed from dried okra seeds and crushed acorns.

Charleston’s seemingly limitless prosperity was now a memory. The shortages of food and household necessities increased their prices and contributed to the inflationary spiral of the Confederate dollar. Charleston’s confidence was vanishing in the face of vulnerability, want and dread- feelings which usually presaged rage and violence.

Life in Charleston would only get worse over the next two years, highlighted by the initiation of daily “Swamp Angel” shelling in the fall of 1863. The city experienced successive waves of whooping cough, smallpox, and yellow fever. A blood debt had been paid by virtually every household. Empty chairs belonging to fathers and sons who had died at Shiloh, to brothers who were dying more slowly, but just as certainly, in rancid Yankee prison camps, to a grandfather dead from pneumonia, an uncle who fell to yellow fever, a sister who wasted away with consumption, or a child dead from typhus.

Charleston had sent more than five thousand men to fight. More than a third had died and the remainder had limped home- aimless, limbless, and angry. Confederate money became worthless for anything other than tindering a fire. Families with missing menfolk were faced with an inability to feed, clothe or shelter their children. Shattered families unable to flee turned to begging, thieving, and prostitution to survive while their emaciated and feral children foraged for food in piles of debris.

The war had been brought to Charleston by ambitious men seeking profit and prestige. They stirred passionate prejudices, defiant in their defense of slavery behind the mantra of states’ rights, racial superiority, and highly selected Biblical passages. They feasted on their less informed and less invested countrymen. They anointed themselves with sanctity and virtue and took their chances on a grab for power and personal reward. The possibility of failure, and the immense suffering it would bring, was dismissed with thoughtless bravado by elite Southern nationalists who comforted themselves with the certainty that any failure would be cushioned by wealth and connections.

Secession was a gamble, and as every gambler knows, it is always best to play with someone else’s money.

For more about the collective madness that led to secession and the consequences of that rebellion to Charleston and the South, please consider reading Roger Newman’s new Civil War historical fiction novel, Will O’ the Wisp: Madness, War, and Recompense available at Amazon, Kindle, Barnes and Nobel, from A-Argus Books, and at www.RogerBNewman.com.