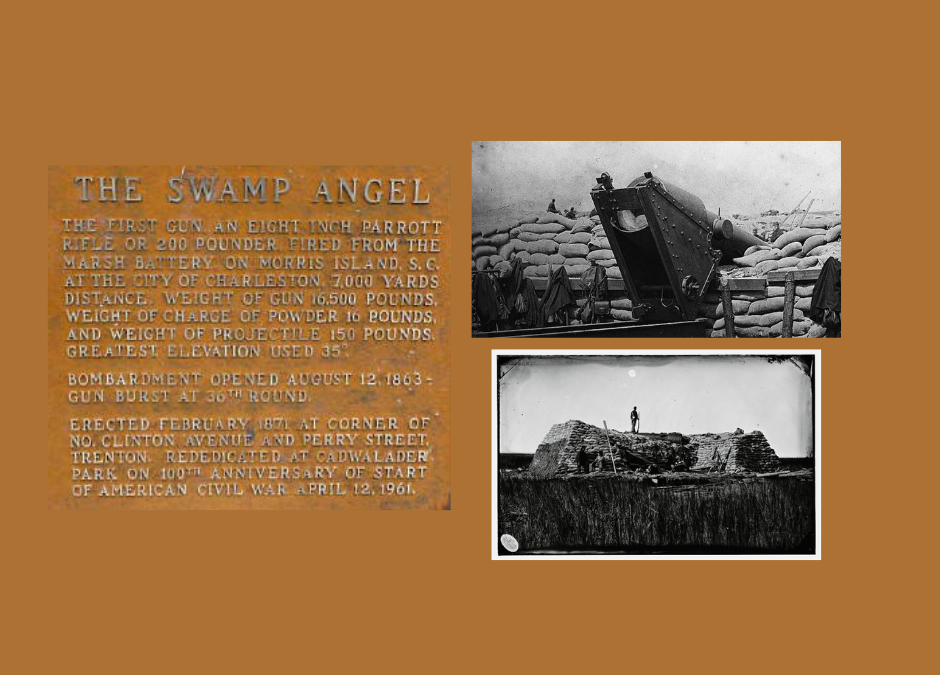

By the fall of 1863, Charleston faced a new and unprecedented threat. With the capture of Morris Island, the Union Army constructed a long-range, two-hundred-pound Parrott rifle hidden in the Morris Island marsh grass. The cannon was dubbed the “Swamp Angel” and could hurl ten-pound shells into downtown Charleston from more than a mile away.

With the “Swamp Angel” prepared to reign over the city, the Union demanded Charleston’s immediate surrender which was summarily refused by General Pierre G.T. Beauregard, commander of Confederate forces in Charleston. After Beauregard’s rejection of surrender terms, President Lincoln made an unprecedented decision in American history. Lincoln authorized the daily bombardment of Charleston and its civilian population. Never before, and never after until Vietnam, had an American president authorized a sustained bombardment of a civilian population. The North had not forgotten Charleston’s responsibility for firing the first traitorous shots on its own countrymen. Day after day, month after month, for more than 500 days, the Union singled out the city of Charleston for holocaustic revenge.

Only the lower peninsula was within range of the long-range Union gun, so most of Charleston’s residents and businesses relocated north of Calhoun Street. The daily shelling, however, devastated the lower peninsula which became known as the “burnt out district.” Jefferson Davis proclaimed that it was better that Charleston is reduced to “a heap of ruin” than be left as “prey for Yankee spoils.” That malignant wish only failed to be realized due to the technical limitations of cannon casting, charge size, and range.

Ultimately, however, the “Swamp Angel” was far more a psychological weapon than a military one. The self-congratulatory speeches and brass bands that had previously resounded up and down Broad Street just three years prior had now been replaced by silence. A silence interrupted only by the now-familiar banshee’s scream of the “Swamp Angel’s” terror. The defiance to Federal governance that had arisen in Charleston had now faded in the face of daily shelling.

How did Charleston survive its siege and how did it find the means to rebuild? You can find some of the answers in the new Civil War historical fiction novel, Will O’ the Wisp: Madness, War, and Recompense by Roger Newman.