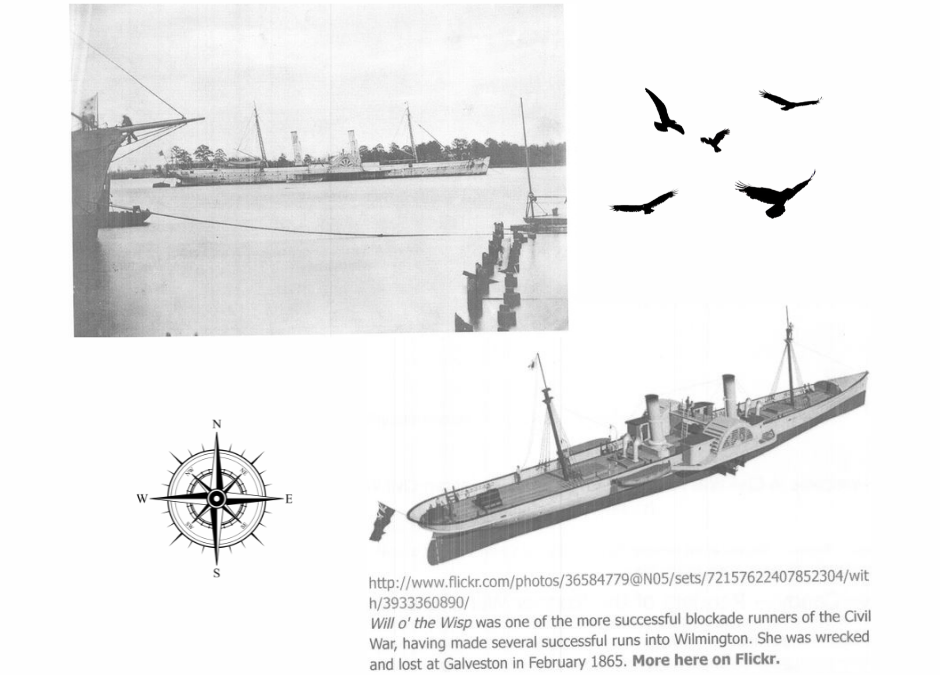

A good friend recently sent me an e-mail with a picture of an actual Civil War blockade runner named “Will O’ the Wisp” which sailed from Wilmington, N.C. and was run sunk late in the war. In my recently published historical fiction novel, “Will O’ the Wisp: Madness, War, and Recompense”, I did not know that the name had already been taken. In my novel, I named Captain Jack Holmes’ ship after a Leon Russell album from the 1970’s I particularly enjoyed my fascination with stories of flammable marsh gases (pixie lights) reported by sailors along the Low Country coast.

In doing the background research for my novel, I was impressed by how little is written about the vital but uniquely dangerous work performed by Southern blockade runners during the Civil War. The cat and mouse battles between the blockade runners (known derisively as “black snakes”) and the ships of the Union Blockading Squadron are mentioned infrequently in the books describing Civil War Naval Warfare.

One reason for this may be that true battles between blockaders and the blockade runners were rare to non-existent. The blockade runners were built for speed and stealth, and they had no intention of exchanging fire with Federal blockaders. They carried no heavy armaments and not an eighth of an inch of iron to protect them from Union cannon. The unfortunate blockade runner who failed to slip past the Federal crescent either turned tail and ran back to the safety of the Charleston harbor and Fort Sumter’s big guns were run aground against the barrier islands or burned to the waterline to prevent their cargo from falling into enemy hands.

The South knew that European arms, munitions, and other industrial products would be their lifeblood in a war against the more populous and industrialized North. Without massive European support, conflict with the North would invariably become a war of attrition that the South could not win. That European support would come in exchange for the ample natural resources offered by the more agrarian South. Charleston’s warehouses were filled with Sea Island cotton, Christ Church timber, turpentine, linseed oil, grains, ham, bacon, and lard. With more than 3,000 miles of Southern coastline, the lumbering men-of-war of the moth-eaten U.S. Navy would be no threat to experienced and resourceful captains with a fleet of swift, powerful, and elusive blockade runners.

The best of the blockade runners were long and narrow with the graceful looks of a yacht with dual side paddlewheels and top-of-the-line English oscillating steam engines. The pilothouse was located just behind sharply angled and telescoping smokestacks which could be lowered to the deck to minimize the runner’s stamp on the horizon. The long, low hull only showed 8 to 10 feet above the waterline and was usually painted a dark blue-gray. The low silhouette and minimal masting allowed the blockade runner to be overlooked at dusk and virtually disappear at night.

Even during the day, the blue-gray color blended with the sea and sky at the merge of the horizon. High-quality Welsh anthracite coal was burned whenever possible yielding only thin white smoke. When steam had to be blown off, it was done underwater, muffling the discharge. Most blockade runners looked fast and those looks were not deceiving. The fastest of the runners could reach a maximum of 15 or 16 knots, even fully loaded, allowing them to sprint across the South Atlantic to the Bahamas, Bermuda, or Cuba. In those neutral ports, the blockade runners would exchange cargo with trans-Atlantic European cargo ships.

Even with those advantages, blockade runners rarely ventured from the port during daylight hours. On moonless and cloudy nights the runners would come out to play. Speed and invisibility were their advantages and their lack of armor assured that they could outrun anything in the Union Atlantic Squadron. Captains and pilots needed to be intimate with the coastline. They had to be able to thread a needle between Union sentinels, cross a shallow bar, and hit a narrow harbor channel in total darkness without lights or cues from a coastline so flat and featureless that the first sign of proximity was often a thin white ribbon of riffling surf.

Lights or smoking on deck were strictly prohibited. Light from the engine room hatchways was blocked by heavy tarpaulins amplifying the heat in the ovens where the firemen and coal heavers labored. Even the pinnacle was shrouded so that the helmsman had to peer into a small conical aperture to see the dimly illuminated compass. The blockade runner was a black hole in the water, undetectable except for the muffled engines and the rhythmic beat of the paddle floats which were quieted by extra canvas tarps hung over the paddlewheel boxes. On such nights, a well-captained blockade runner could pass within 100 yards of a Union lookout without being detected.

Eternal vigilance is an unsustainable standard order. Federal lookouts spent tedious hour after hour on high alert peering into blackness for a sign of a nearly invisible “black snake.” Among Union captains, assignment to the Charleston blockade was considered the worst possible duty. Federal captains referred to Charleston as a “rat hole” due to the multitude of barrier islands, navigable rivers, and inlets up and down the Low Country coast. Realizing that their naval careers depended on their interdiction success, assignment to the Charleston blockade was highly demoralizing to both captains and crews.

Commander John Downes of the Federal gunboat Huron sent the following communication back to the U.S. Department of the Navy. “I wish I could impress upon you some faint notion of how disgusting it is to us, after going through the anxieties of riding out a black, rainy, windy night at three fathoms of water, with our senses on alert for the sound of paddles or sight of miscreant violation of our blockade, and when morning comes to behold him lying placidly inside of Fort Sumter as if getting there was the most natural thing in the world and the easiest.”

Unfortunately, the initial success of the blockade runners could not be sustained. As the war progressed, the number and quality of the blockading squadrons improved. Rusted junkers liberated from the New England whaling fleet were replaced by newer, faster steam-powered warships with ever more imposing firepower. The number of successful blockade runs fell progressively as the Federal noose continuously tightened around the Southern ports.

To learn more about the Southern blockade runners and enjoy a Civil War blockade running adventure, please check out my new novel, “Will O’ the Wisp: Madness, War, and Recompense”, published by A-Argus Books and W&B Publishing. It is also available via Amazon, Kindle, and Barnes and Noble.